Honey, there’s a Ukrainian drone in the kitchen

Ukraine needs one million of them to fight the Russians. Enter the modern 'Victory Garden,' akin to what Brits did at home to help with the war: Violetta assembles drones next to her pots and pans.

Editor’s Note: Things are looking bleak in Ukraine. Pessimism is higher than at any time since the full-scale invasion began. Fight back by helping us bring our unique, empathetic approach to journalism to people thousands of miles away!

Violetta Oliinyk has spent much of her life making delicate pieces of art.

However, since the war started, she no longer perfects sophisticated jewelry.

Instead, Violetta now assembles drones for the Ukrainian army in her kitchen.

At the beginning of this year, Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation urged Ukrainians to assemble drones at home to create a decentralized network of drone manufacturing.

In some ways, Ukrainian home drone production resembles the victory gardens of the British WWII home front, when people were told to ‘Dig for Victory’, and grow vegetables in their backyards to help the war effort.

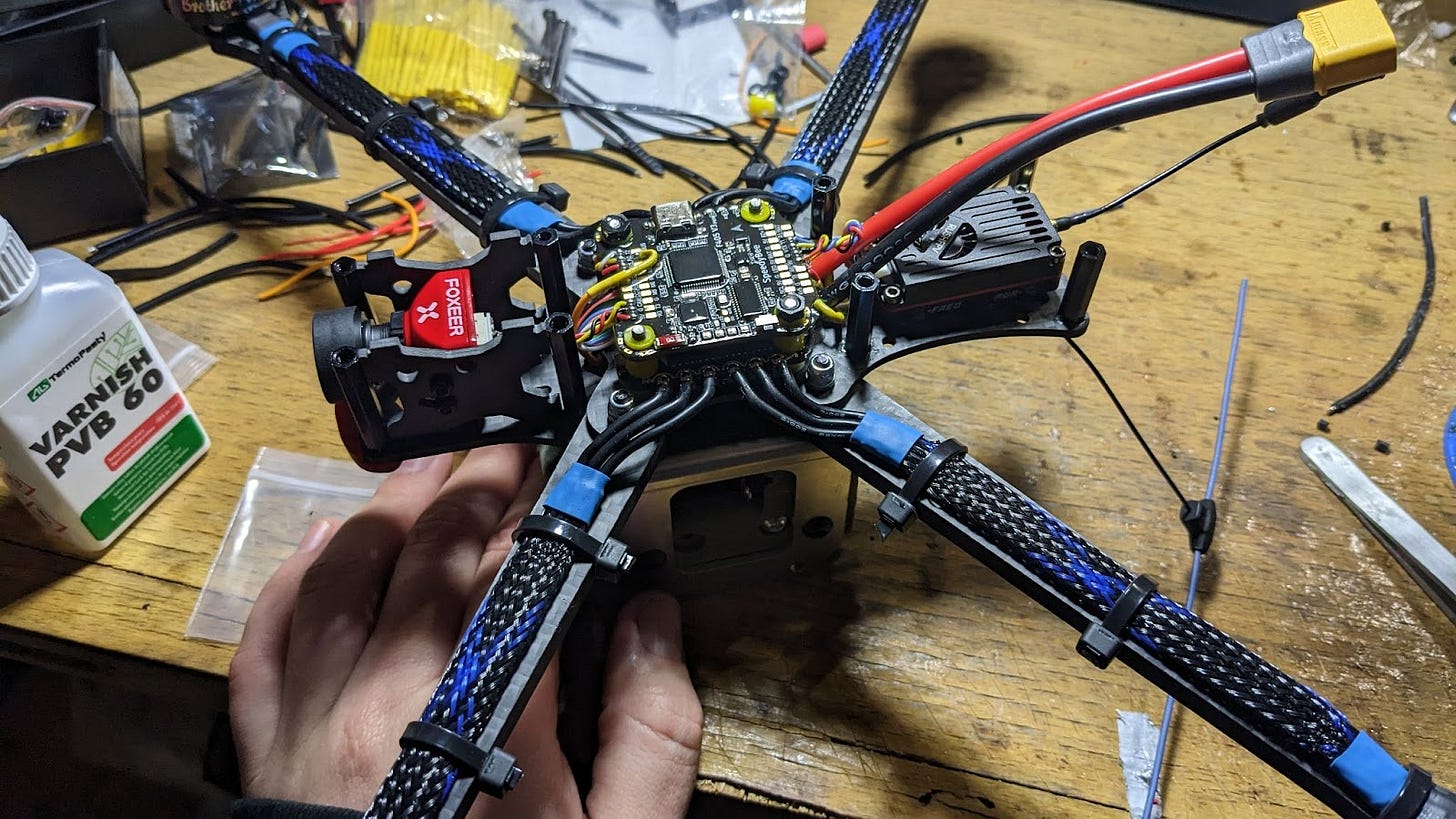

There are some differences, of course, including the technological complexity: first-person view (FPV) drones are advanced devices, equipped with an onboard camera which livestreams the view from the aircraft to a pilot.

Homemade FPVs have become another line in the long list of items that thousands of Ukrainians are producing at home: from hand-made chemical heating pads for foot warmth, to camouflaged sniper coats, to 3D-printed mine detectors.

Decentralized production has its upsides. It protects manufacturers from the effects of regular Russian airstrikes, and trains a generation of drone engineers, who have the potential to scale up production on their own. However, there’s a downside: it can’t compete with the efficiency, or the low cost, of industrial manufacturing.

For Ukraine, this ambitious endeavor seems to be the only way to domestically produce a million drones, a goal announced by President Zelenskyy. That means it could well be the only way to ensure the nation's survival in the war with the prevailing Russian army.

Initially deployed as a reconnaissance tool, FPV drones were swiftly enhanced to carry grenades, which turned them into a mobile and guided weapon.

Having dedicated most of her 28 years to mastering a diverse range of skills, from stained glass production to jewelry, Violetta never imagined herself assembling kamikaze drones until war broke out in her country.

The news of the Russian invasion reached Violetta on her way back from a brief tourist trip to Europe, where she was seeking distraction from pervasive speculation about the looming war. Returning home amid the uncertainty of those initial days, Violetta faced another, personal challenge – her father and two brothers decided to join the Ukrainian army.

It wasn’t the first time she’d faced the realities of war. Her family previously fought against Russians following incursions in 2014. Violetta transformed her experience on awaiting their return from the battlefield into an art performance: ‘Brothers,’ held in Poland.

"I've always believed in the profound impact of art on viewers' consciousness. However, I've been somewhat disappointed by art’s limited abilities to support the army... Assembling drones or making trench candles seems far more effective than holding exhibitions in art galleries," Violetta told The Counteroffensive.

Drone manufacturing found Violetta unexpectedly. In November 2023, Violetta’s family on the frontlines sent her an order to purchase one – and meticulous research led her to the idea that making one herself was the quickest way to fulfill their wish.

In autumn 2023, the Ukrainian social initiative Victory Drones cooperated with the drone manufacturing brand ‘Vyriy’ to launch the People’s FPV project, offering free drone assembly courses for civilians.

The course has gained over 17,000 participants, who can receive free feedback from lecturers and an opportunity to submit their self-made 7-inch FPV drones for testing. They’ve produced 350 drones as of the beginning of February.

For Violetta, the immersion into drone assembly took only one evening. She enrolled in the course to get access to its video lessons and list of materials, and meticulously watched the videos to identify missing details.

Those few hours marked the beginning of full-time work on drone assembly, during which Violetta has assembled 23 FPV and bomber drones, all successfully tested and deployed for combat missions on the frontlines.

Despite her background in the arts being instrumental in soldering, Violetta believes that drone assembly skills can be mastered by anyone who can handle a blowtorch, screwdriver, and a tweezer.

The average cost of a drone parts set ranges from $420 USD for an FPV, used for reconnaissance and kamikaze missions; to $530 USD for a reusable bomber drone, deployed for attacks.

Procuring parts remains a significant challenge. Due to inflated prices and high demand in wartime Ukraine, Violetta usually orders sets of components from Chinese marketplaces. But this comes with having to deal with month-long shipping, customs duties management, and the constant risk of receiving defective items or having the pre-paid orders canceled.

The assembly process takes several hours, after which Violetta uploads a pre-made computer file to install software. Then she conducts preliminary testing: examining motor functionality and temperature, and verifying radio and video transmission.

Subsequently, the drone leaves Violetta’s workshop — once dedicated to jewel-crafting — and undergoes final testing by drone pilots before deployment on combat missions.

Violetta is also a burgeoning drone pilot these days, learning from long periods testing FPVs. Having mastered the fundamentals of drone assembly, she now focuses on learning how to equip her products with thermal imagers and perfecting final flybys.

“There’s the constant risk of being hit by missiles, Shahids [Iranian-made kamikaze drones widely deployed by Russia], as well as sabotage threats,” she said. “If this production is dispersed enough that everyone assembles a drone in their own home, we are all relatively safe – as long as there is no large storage or centralized production.”

Violetta’s FPV drone attacking a Russian dugout

An unexpected ally in her family is helping with the project. Violetta's 82-year-old grandfather, who aspired to join territorial defense troops early in the invasion but was rejected due to his age, fervently supports her initiative.

Having taught model aviation long before her birth, he assisted his granddaughter with drone assembly but had to quit because of poor eyesight. Instead, he has poured all of his energy into convincing the city council to allocate funds for purchasing drones for Ukrainian servicemen and even organized drone assembly training in a local school.

“You have to understand the responsibility that [drone assembly] implies. Your task is to assemble a drone that will fly and do its job. After all, it's a very important item, not a decoration or a kind of construction set,” said Violetta, whose days now mainly consist of taking orders from soldiers, sending and receiving packages, and making drones in her kitchen.

And despite the fact that her tools now shape plastic rather than silver, she remains exactly who she used to be – a jeweler in wartime.

After the paywall: Ukrainian military operations… in Sudan? And Myroslava takes you behind-the-scenes to a drone testing facility, where soldiers try out homemade drones before they’re taken to the battlefield.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Counteroffensive with Tim Mak to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.