Your favorite Christmas carol's hidden Ukrainian history

How one woman reconnected with her Ukrainian ancestry by learning the original lyrics. Meanwhile, Oksana visits Kyiv’s largest synagogue to learn a Hanukkah lesson from its rabbi.

Editor’s Note: In a festive, giving mood? Share a Counteroffensive subscription with a friend, either a gift paid subscription, or refer friends for a free subscription and earn rewards.

And if you think what we’re doing is important, and you haven’t yet, please upgrade now!

There’s a Ukrainian Christmas carol that you hear every year – but you probably don’t know its origins.

As you do your holiday shopping or watch television, you’ll hear it in the background.

Over the years, it’s been Americanized – and commercialized:

It’s a song called ‘Shchedryk’ – a Ukrainian tune, known to the U.S. and the Western world as ‘Carol of the Bells’.

Once they’re in your head, the insistent lyrics stay there:

“Hark how the bells / Sweet silver bells / All seem to say. Throw cares away…”

This song, loved by millions, has a unique, deeply personal meaning to Maria, an American with Ukrainian ancestry, weaving camouflage nets in a volunteer center in Kyiv.

For her, just like thousands of Ukrainian-Americans, the beloved Christmas hit embodies ancestral pride, inseparable from deep-rooted historical trauma. ‘Schedryk’ is a lifeline to endangered Ukrainian language and culture, a carol that embodies Ukraine's soft power influence in the world.

Here it is in English and Ukrainian, where the lyrics are different:

The Ukrainian version has a title that roughly translates to ‘Bountiful Evening’, and takes the listener to the Ukrainian countryside. There a bird flies into a master’s house, and tells him to look with wonder at his newborn lambs and beautiful wife.

"When I would read the last part, I would always cry, and I never understood why because I was like, I've never even been there,” she said. “But I always felt nostalgic, like I was torn away from my mother before I ever got to know her," Maria said.

It reminded her of the place her family had been forced out of.

The globally-loved melody was written by Ukrainian composer Mykola Leontovych and first presented to a broad audience in 1916, in Kyiv, then a part of the Russian Empire.

Just three months after the song's sensational premiere, the fading empire was rocked by a revolution and protracted civil war that paved the way for the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic.

Guided by the hope of winning allies who would help them deter advancing Russian troops, in 1919 Ukraine’s government launched an ambitious musical tour to Europe, where ongoing peace talks were redrawing the map of the post-WWI world.

As their acclaimed orchestra was moving further across Western Europe, gaining worldwide fame, the Russians were advancing westward into Ukraine.

By the time the renowned Ukrainian choir premiered their crown song at Carnegie Hall in October 1922, the Russian conquest had been completed.

That New Year's Eve, Ukrainian performers of the Christmas hit-in-the-making had lost their citizenship overnight, and settling in the US remained their only salvation from looming communist repressions.

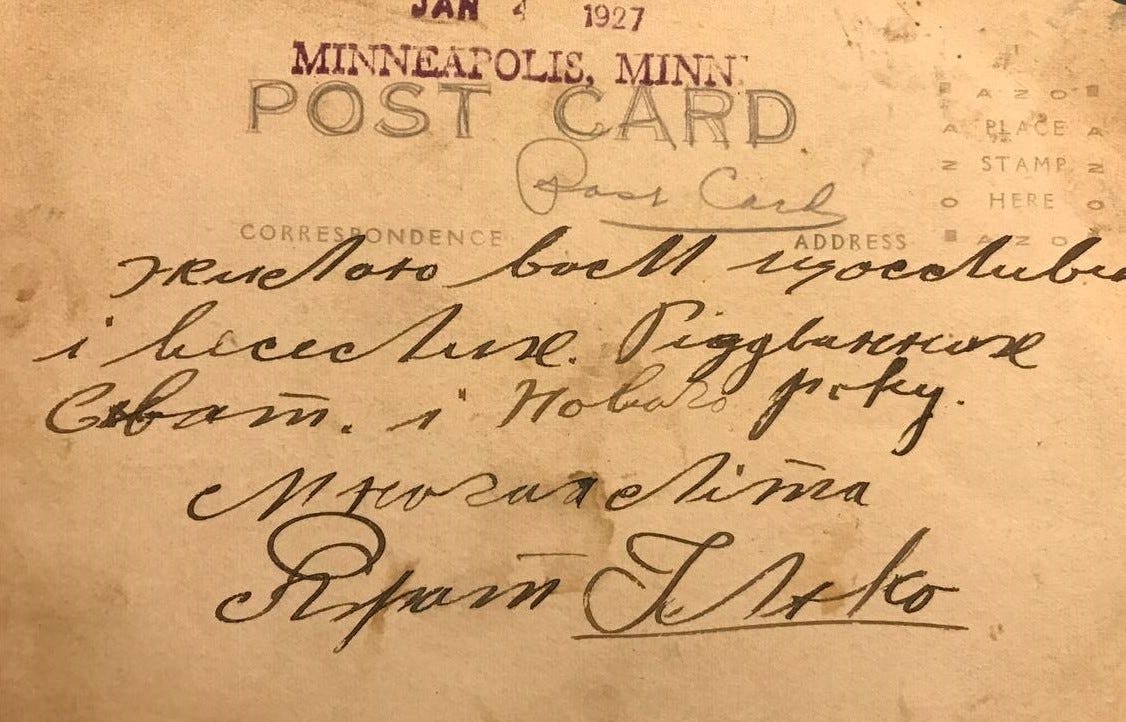

Around the same time when the ‘Shchedryk’ orchestra were taking their first steps as American citizens, Maria’s family was trying to adjust to life in the United States, having fled a similar Russian threat.

In 1906, Maria’s Ukrainian great-grandmother Kateryna Ivanuik, aged six, arrived in New York. The family came from the fringes of the Russian and the Austrian empires that suffered from exceptional poverty and occasional raids from the Russian soldiers.

In one of those assaults, a violent clash occurred between a Russian soldier and one of Kateryna's relatives, and the soldier was killed in self-defense. Fearing retribution from Russian authorities, the whole family left for the unknown land that was destined to become their safe haven for the next century.

The pain of forced migration permeated her family so deeply that Catherine's sense of loss constantly broke through Maria’s peaceful childhood. She felt it almost physically every time her great-grandma taught her ‘Carol of the Bells’ from Ukrainian-themed books.

When Maria graduated from high school, her Ukrainian-speaking grandmother Sofia told her she could ask whatever she wanted about the family’s history.

Ukrainian neighbors had moved in nearby, and Maria excitedly asked if she could hear them speaking Ukrainian together. Her grandmother agreed.

But Sofia was a second-generation American, and stumbled with her Ukrainian language, fumbling to find the words to communicate.

"And then I could see the pain and shame,” Maria recalled. “The lady looked really disappointed, and it hurt me so much that I had put my grandma in that position."

Numerous similar situations, occurring throughout her life, shaped Maria's perception of her Ukrainian identity as an endangered treasure, inseparable from loss:

"It felt like something that if I didn't hold it and protect it, it would be gone," Maria said. "And the way that my family would talk about it, it seemed like something way too important to let go... we have something so special that people are going to actively try and kill it."

This idea solidified with Russia's 2014 invasion of Ukraine, which transformed her family's ancestral bitterness toward Russia, into a terrifyingly realistic survival life lesson.

"It felt like watching your loved one being beaten up, and you just can't do anything about it. I thought I wasn't going to allow those animals to keep my family away from our homeland twice because they had already done it once,” Maria reflected.

Residing in Puerto Rico at that time, Maria faced the news while working for a Ukrainian tech company. Around that time, she accomplished a lifelong dream to study her ancestral tongue — with ‘Shchedryk’ becoming the first song she learned in Ukrainian.

In 2022, about a century after ‘Shchedryk’ first reached U.S. shores to become an internationally recognized symbol of Christmas, Maria went the other way and stepped on Ukrainian soil for the first time. Then, just like a century ago, Ukraine was facing a Russian advance similar to the one that has forced both her family and America's favorite carol out of the country of their origin.

Coming with one small suitcase, carrying her childhood Ukraine-themed books among other precious possessions, Maria later settled in the embattled capital in April 2023. Despite constant life-threatening danger from air raids, she needed only a few weeks and one special event to make the most significant choice of her life:

"I remember the Vyshyvanka day in May, when we had been bombed for like the 20th time the night before… I was exhausted. Everyone was exhausted. And I remember walking down the street, feeling tired, and seeing everyone around me clearly tired. But we were all walking to where we needed to go, wearing our Vyshyvankas [embroidered shirts]. And I felt that this is where I belong."

Eighteen months after those events, Maria — a proud fourth-generation American — is teaching military English in Ukraine, where she intends to spend the rest of her years. In addition to volunteering for the Ukrainian army, she is preparing to apply for Ukrainian citizenship, which requires her US passport to be renounced.

In over a century since her family's migration to the US, Maria will be the first family member to celebrate Christmas in their ancestral village, in the Ternopil region of Western Ukraine.

She’ll be around her Ukrainian cousins, one of whom is expecting a new baby to arrive just before New Year's Eve.

Just like the promise of new life in ‘Shchedryk.’

NEWS OF THE DAY

Good morning to readers. Kyiv remains in Ukrainian hands.

Some people ask why we still use that tagline, nearly two years in. I explain why, after the paywall.

Here’s why one subscriber decided to sign up for a paid subscription:

"Iʼm a subscriber because youʼve shown you have an exceedingly rare quality among war correspondents: caring about the experience of the people that the war is inflicted upon more than the goals and objectives of the people who doing the inflicting. I want to stay informed, but I donʼt care to read transcriptions of memos from the public affairs office."

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Counteroffensive with Tim Mak to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.